Hello! This week I started building some choose-your-own-adventure-style puzzles about debugging networking problems. I’m pretty excited about it and I’m trying to organize my thoughts so here’s a blog post!

The two I’ve made so far are:

I’ll talk about how I came to this idea, design decisions I made, how it works, what I think is hard about making these puzzles, and some feedback I’ve gotten so far.

why this choose-your-own-adventure format?

I’ve been thinking a lot about DNS recently, and how to help people troubleshoot their DNS issues. So on Tuesday I was sitting in a park with a couple of friends chatting about this.

We started out by talking about the idea of flowcharts (“here’s a flowchart that will help you debug any DNS problem”). I’ve don’t think I’ve ever seen a flowchart that I found helpful in solving a problem, so I found it really hard to imagine creating one – there are so many possibilities! It’s hard to be exhaustive! It would be disappointing if the flowchart failed and didn’t give you your answer!

But then someone mentioned choose-your-own-adventure games, and I thought about something I could relate to – debugging a problem together with someone who knows things that I don’t!

So I thought – what if I made a choose-your-own-adventure game where you’re given the symptoms of a specific networking bug, and you have to figure out how to diagnose it?

I got really excited about this and immediately went home and started putting something together in Twine.

Here are some design decisions I’ve made so far. Some of them might change.

design decision: the mystery has 1 specific bug

Each mystery has one very specific bug, ideally a bug that I’ve actually run into in the past. Your mission is to figure out the cause of the bug and fix it.

design decision: show people the actual output of the tools they’re using

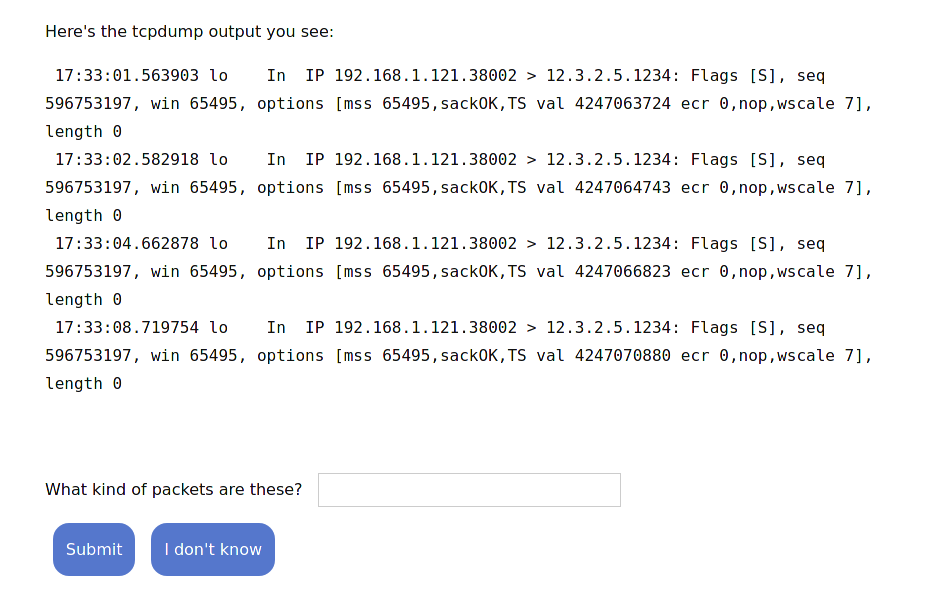

All of the bugs I’m starting with are networking issues, and the way you solve them is to use various tools (like dig, curl, tcpdump, ping, etc) to get more information.

Originally I thought of writing the game like this:

- You choose “Use curl”

- It says “You run

<command>. You see that the output tells you<interpretation>“

But I realized that immediately interpreting the output of a command for someone is extremely unrealistic – one of the biggest problems with using some of these command line networking tools is that their output is hard to interpret!

So instead, the puzzle:

- Asks what tool you want to use

- Tells you what command they ran, and shows you the output of the command

- Asks you to interpret the output (you type it in in a freeform text box)

- Tells you the “correct” interpretation of the output and shows you how you could have figured it out (by highlighting the relevant parts of the output)

This really lines up with how I’ve learned about these tools in real life – I don’t learn about how to read all of the output all at once, I learn it in bits and pieces by debugging real problems.

design decision: make the output realistic

This is sort of obvious, but in order to give someone output to help them diagnose a bug, the output needs to be a realistic representation of what would actually happen.

I’ve been doing this by reproducing the bug in a virtual machine (or on my laptop), and then running the commands in the same way I would to fix the bug in real life and paste their output.

Reproducing the bug isn’t always easy, but once I’ve reproduced it it makes building the puzzle much more straightforward than trying to imagine what tcpdump would theoretically output in a given situation.

design decision: let people collect “knowledge” throughout the mystery

When I debug, I think about it as slowly collecting new pieces of information as I go. So in this mystery, every time you figure out a new piece of information, you get a little box that looks like this:

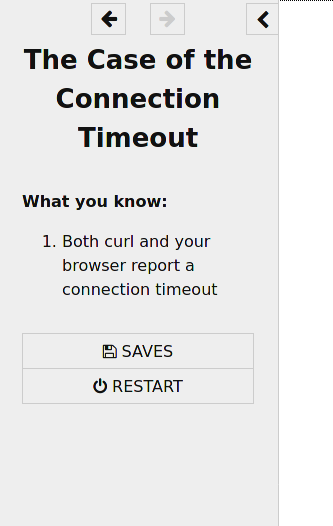

And in the sidebar, you have a sort of “inventory” that lists all of the knowledge you’ve collected so far. It looks like this:

design decision: you always figure out the bug

My friend Sumana pointed out an interesting difference between this and normal choose-your-own-adventure games: in the choose-your-own-adventure games I grew up reading, you lose a lot! You make the wrong choice, and you fall into a pit and die.

But that’s not how debugging works in my experience. When debugging, if you make a “wrong” choice (for example by making a guess about the bug that isn’t correct), there’s no cost except your time! So you can always go back, keep trying, and eventually figure out what’s going on.

I think that “you always win” is sort of realistic in the sense that with any bug you can always figure out what the bug is, given:

- enough time

- enough understanding of how the systems you’re debugging work

- tools that can give you information about what’s happening

I’m still not sure if I want all bugs to result in “you fix the bug!” – sometimes bugs are impossible to fix if they’re caused by a system that’s outside of your control! One really interesting idea Sumana had was to have the resolution sometimes be to tell someone else (like your ISP) about the issue, which made me think about how it’s a useful skill to be able to write a really clear and convincing bug report so that the people with the ability to fix the bug will be able to easily recognize that you’ve accurately diagnosed the issue.

design decision: include red herrings sometimes

In debugging in real life, there are a lot of red herrings! Sometimes you see something that looks weird, and you spend three hours looking into it, and then you realize that wasn’t it at all.

One of the mysteries right now has a red herring, and the way I came up with it was that I ran a command and I thought “wait, the output of that is pretty confusing, it’s not clear how to interpret that”. So I just included the confusing output in the mystery and said “hey, what do you think it means?”.

One thing I like about including red herrings is that it lets me show how you can prove what the cause of the bug isn’t which is even harder than proving what the cause of the bug is.

design decision: use free form text boxes

Here’s an example of what it looks like to be asked to interpret some output. You’re asked a question and you fill in the answer in a text box.

I think I like using free form text boxes instead of multiple choice because it feels a little more realistic to me – in real life, when you see some output like this, you don’t get a list of choices!

design decision: don’t do anything with what you enter in the text box

No matter what you enter in the text box (or if you say “I don’t know”), exactly the same thing happens. It’ll send you to a page that tells you the answer and explains the reasoning. So you have to think about what you think the answer might be, but if you get it “wrong”, it’s no big deal.

The reason I’m doing this is basically “it’s very easy to implement”, but I think there’s maybe also something nice about it for the person using it – if you don’t know, it’s totally okay! You can learn something new and keep moving! You don’t get penalized for your “wrong” answers in any way.

design decision: the epilogue

At the end of the game, there’s a very short epilogue where it talks about how likely you are to run into this bug in real life / how realistic this is. I think I need to expand on this to answer other questions people might have had while going through it, but I think it’s going to be a nice place to wrap up loose ends.

how long each one takes to play: 5 minutes

People seem to report so far that each mystery takes about 5 minutes to play, which feels reasonable to me. I think I’m most likely to extend this by making lots of different 5-minute mysteries rather than making one really long mystery, but we’ll see.

what’s hard: reproducing the bug

Figuring out how to reproduce a given bug is actually not that easy – I think I want to include some pretty weird bugs, and setting up a computer where that bug is happening in a realistic way isn’t actually that easy. I think this just takes some work and creativity though.

what’s hard: giving realistic options

The most common critique I got was of the form “In this situation I would have done X but you didn’t include X as an option”. Some examples of X: “ping the problem host”, “ssh to the problem host and run tcpdump there”, “look at the log file”, “use netstat”, etc.

I think it’s possible to make a lot of progress on this with playtesting – if I playtest a mystery with a bunch of people and ask them to tell me when there was an option they wish they had, I can add that option pretty easily!

Because I can actually reproduce the bug, providing an option like “run

netstat” is pretty straightforward – all I have to do is go to the VM where

I’ve reproduced the bug, run netstat, and put the output into the game.

A couple of people also said that the game felt too “linear” or didn’t branch enough. I’m curious about whether that will naturally come out of having more realistic options.

how it works: it’s a Twine game!

I felt like Twine was the obvious choice for this even though I’d never used it before – I’d heard so many good things about it over the years.

You can see all of the source code for The Case of the Connection Timeout in connection-timeout.twee and common.twee, which has some shared code between all the games.

A few notes about using Twine:

- I’m using SugarCube, the sugarcube docs are very good

- I’m using tweego to translate the

.tweefiles in to a HTML page. I started out using the visual Twine editor to do my editing but switched totweegopretty quickly because I wanted to use version control and have a more text-based workflow. - The final output is one big HTML file that includes all the images and CSS and Javascript inline. The final HTML files are about 800K which seems reasonable to me.

- I base64-encode all the images in the game and include them inline in the file

- The Twine wiki and forums have a lot of great information and between the Twine wiki, the forums, and the Sugarcube docs I could pretty easily find answers to all my questions.

I used pretty much the exact Twine workflow from Em Lazerwalker’s great post A Modern Developer’s Workflow For Twine.

I won’t explain how Twine works because it has great documentation and it would make this post way too long.

some feedback so far

I posted this on Twitter and asked for feedback. Some common pieces of feedback I got:

things people liked:

- maybe 180 “I love this, this was so fun, I learned something new”

- A bunch of people specifically said that they liked learning how to interpret tcpdump’s output format

- A few people specifically mentioned that they liked the “what you know” list and the mechanic of hunting for clues and how it breaks down the debugging process.

some suggestions for improvements:

- Like I mentioned before, lots of people said “I wanted to try X but it wasn’t an option”

- One of the puzzles had a resolution to the bug that some people found unsatisfying (they felt it was more of a workaround than a fix, which I agreed with). I updated it to add a different resolution that was more satisfying.

- There were some technical issues (it could be more mobile-friendly, one of the images was hard to read, I needed to add a “Submit” button to one of the forms)

- Right now the way the text boxes work is that no matter what you type, the exact same thing happens. Some people found this a bit confusing, like “why did it act like I answered correctly if my answer was wrong”. This definitely needs some work.

some goals of this project

Here’s what I think the goals of this project are:

- help people learn about tools (like tcpdump, dig, and curl). How do you use each tool? What questions can they be used to answer? How do you interpret their output?

- help people learn about bugs. There are some super common bugs that we run into over and over, and once you see a bug once it’s easier to recognize the same bug in the future.

- help people get better at the debugging process (gathering data, asking questions)

what experience is this trying to imitate?

Something I try to keep in mind with all my projects is – what real-life experience does this reproduce? For example, I kind of think of my zines as being the experience “your coworker explains something to you in a really clear way”.

I think the experience here might be “you’re debugging a problem together with your coworker and they’re really knowledgeable about the tools you’re using”.

that’s all!

I’m pretty excited about this project right now – I’m going to build at least a couple more of these and see how it goes! If things go well I might make this into my first non-zine thing for sale – maybe it’ll be a collection of 12 small debugging mysteries! We’ll see.